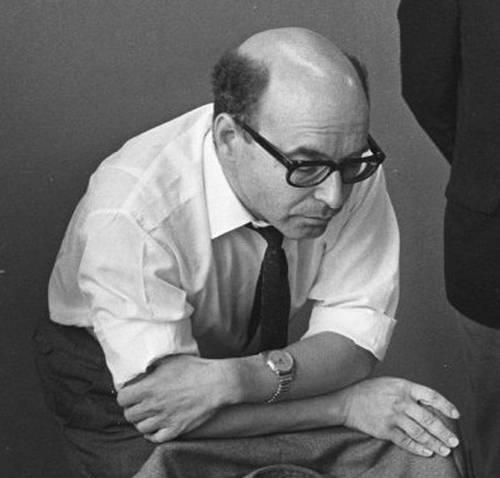

Today is 100 years since the birth of David Bronstein.

David Bronstein was an outstanding grandmaster, and yet – a unique case for a man who almost became world champion – his immediate contribution to popularizing chess is no less important.

Bronstein authored several great books. Along with Zurich-1953 (written for the most part by his senior friend and mentor Boris Vainstein), I would mention the remarkable “200 Open Games”. And how many wonderful and memorable articles he wrote how many insightful predictions! Judge for yourself:

In his essays “On the Way to the Electronic Grandmaster” and “Chess of the Third Millennium”, Bronstein predicted much of modern computer and online chess, albeit in the terminology of 1978 (the book “A Beautiful and Furious World”, co-authored with Smolyan).

“…A chess player would use a machine to extensively analyze the variants chosen based on his knowledge and intuition to test strategic ideas and control errors. It would have added at least 500 points on the professor A. Elo’s rating scale.”

Photo: Eric Koch pour Anefo — Dutch National Archives, The Hague

Photo: Eric Koch pour Anefo — Dutch National Archives, The Hague

“Today, we don’t know any chess player, including the world champion, who, having made the first move, can recite all possible variations as he sees them on a tape recorder. But if the best chess players in the world were contesting with a microphone, everyone would hear how beautifully they think. However, FIDE is clueless that by organizing tournaments of talking grandmasters, the federations would gather an appreciative audience of millions. (In this case, you can’t hide your own helplessness behind other people’s moves.) Masters could use television technology to speak to the public in the language of chess symbols in such tournaments. Such a game, among other things, would remove certain inferiority from those playing since the public considers an unexpected move for themselves as a surprise for the grandmaster as well. And with closer contact, the audience would fantasize less and penetrate deeper into highly skilled and creative thinking.”

“It is likely that some publisher will release a game of ‘Chess Tests’ in time. Different positions will pop out of a box for a certain amount of time, while a counter will indicate a score depending on the quickness of the solution choice.”

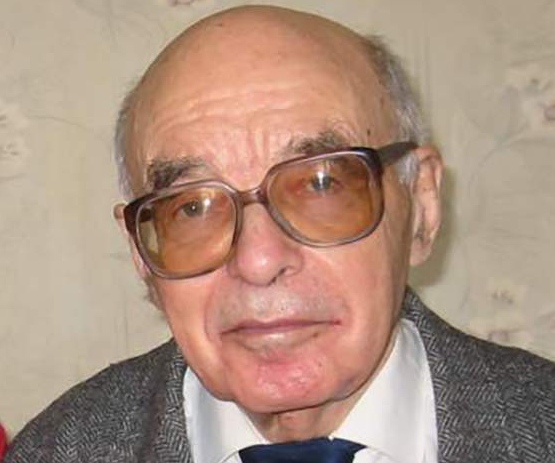

Photo credit: D. Prants, via https://muis.ee

Photo credit: D. Prants, via https://muis.ee

“The Chess House Central Machine Service will appear, and you can join the computer by telephone and play with it if you like – the whole family. After the game, the computer will send you, along with your energy bill, a copy of the game.”

Bronstein was a pioneer in many ways, and it is a pity that he did not become world champion. I think many of his original ideas would have received a much broader appeal.

A pupil of Alexander Konstantinopolsky (by a funny coincidence, also born on February 19), he stood out both in his playing style and opening repertoire. Bronstein, along with Boleslavsky, is credited with introducing the King’s Indian Defense to the top competitive level. Thanks to them, the opening was for some time called the “Ukrainian Defence”, as two friends – Bronstein from Kyiv and Boleslavsky from Dnepropetrovsk – who had worked together since their youth, actually brought this opening into the highest tournament level.

“Devik”, as he was called, played with great panache sacrificing pawns and pieces. The trajectory of his rise was very steep. Who knows how his fate and chess history would have turned out had he preserved the lead in the title match with Botvinnik in 1951? It was 11.5:10.5 on the scoreboard with just two games to play, and all he needed was not to lose. If Bronstein had held on then, many things would have been different.

Having become vice-champion at 27, Bronstein could not overcome the shock of missing this chance.

For another fifteen years after the match, he played at a high level and, most importantly, was bursting with ideas. Rapid chess is also Bronstein’s brainchild and even time increment called Fischer’s was originally spotted by Bronstein in Shogi, and only then, slightly modified, was adapted in chess. There were many other things: his books, where truth is mixed with fantasy but permeated with love for chess, different engaging formats, etc.

Gradually, he got older; his marvelous ideas interspersed with eccentric ones, and more and more often, David reminisced about to the 1951 title match he had failed to win.

This indelible bitterness was present in many of his late speeches and articles. It was felt in talks with him as well. I had a chance to talk to the legendary veteran quite a bit and even received a compliment from him during a game with van Wely (1997). After I made a subtle move, Bronstein, who hung around the table for a long time, waited for me to stand up, took me under the elbow and said in a loud whisper: “You’re playing 21st-century chess!”

Photo: Anne Fürstenberg

Photo: Anne Fürstenberg

He was an eccentric, one-of-a-kind person who talked a lot, sometimes even losing his interlocutor’s attention. Bronstein gushed out most of his interesting ideas in his younger years. David lived a long life, but he was the kind of person who gave out almost the entire stock in the first half of the journey. Still, this alone more than suffices for a place in any chess pantheon. He loved chess passionately into his old age. David loved talking about it. He loved experimenting. He continued to play in tournaments even in his 70s. Bronstein always had a lot of fans, and the organizers opened doors for him. Was he a wise man as the artist portrayed him? Probably not. He was a man capable of thinking up countless original ideas. Sometimes paradoxical. Sometimes deliberately provocative. But they were brilliant and had far-reaching consequences.

He was always in the limelight, no matter what he did, whether it was his brilliant play and top-level skills of a practical player, an array of ideas in the King’s Indian, Dutch, Ruy Lopez and Sicilian, Nimzo-Indian and Queen’s Indian, or his books, which will be relevant as long as chess lives.

Thank you, David Ionovich, we remember you!

Emil Sutovsky, FIDE CEO