The legendary Yugoslav (Serbian) Grandmaster, Borislav Ivkov, passed away in Belgrade at the age of 88. He was not just a master of chess but also a maestro of the written word who sought the meaning of life. Milan Dinic, Editor of the British Chess Magazine, relives the moments with the Serbian legend, a friend of his family, in this distinctive obituary that he kindly shared with us.

Borislav Ivkov was born in 1933 in Belgrade, then the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He became the youth champion of Belgrade at the age of 14, and at the age of 17, he won the first World Junior Championship in Birmingham in 1951. He was awarded the title of Grandmaster in 1955 and for many years was considered one of the strongest Yugoslav and world players, next to Svetozar Gligoric. His peak was in the 1950s (when he was in the top 10 in the world) and in the 1960s.

A stellar career

Ivkov had an outstanding career marked with successes in both national and international events. A three-time champion of Yugoslavia, he qualified for the 1965 Candidates matches (he lost to Bent Larsen) and played four more Interzonal tournaments during the 1960s and 1970s.

The winner of numerous strong tournaments (including Mar del Plata 1955, Buenos Aires 1955, Santiago 1959, Beverwijk 1961, Zagreb 1965, Amsterdam-IBM 1974), Ivkov also took the champion title at the European Senior Individual Championship in Davos in 2006.

Borislav Ivkov was a regular member of the Yugoslav chess team from 1965 until 1980, winning ten team medals in 12 Olympiads (six silver and four bronze medals) and five board medals. He played for Yugoslavia in the European team championships six times, winning three team silvers, one bronze and one gold board medal. Ivkov also took part in the historic match USSR vs the Rest of the World (1970), playing on the tenth board.

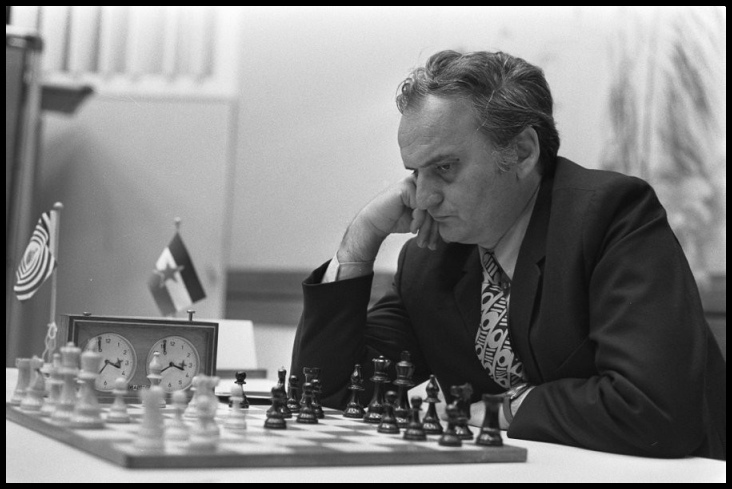

Photo: Dutch National Archive

Photo: Dutch National Archive

At these and many other events Ivkov was ahead of the likes of Gligoric, Najdorf, Larsen, Uhlmann, Portisch, Bronstein, Petrosian (when he was World Champion), Stein, Korchnoi and Jansa. Several world champions fell prey to Ivkov, including Bobby Fischer, Tigran Petrosian, Vasily Smyslov, Mikhail Tal and Anatoly Karpov. He also drew all of his games with Botvinnik.

A great writer

Apart from being a world-class grandmaster, Borislav Ivkov was known as a prolific writer.

In his native Serbia, he published several books about chess and life, including ‘My sixty-four years in chess’, ‘Black on white’, ‘Mesmerized by chess’, and ‘Parallels 1 and 2’.

His books are dedicated to his career in chess but also – to the lives and characters of great players, the people he met, the places he visited and the experiences he had.

In one of the books, instead of a foreword, he wrote a few joking lines dedicated to my father: “Vladan Dinic, the bard of Yugoslav journalism and a well-known chess lover, said to me: ‘From all of your books you may be able to put together one decent book!” Recently, he told my father that he was working on another book. We don’t know if he finished it or not…

A big Character

Borislav Ivkov – or, Bora, as he was known – a true gentleman, one of those people who can charm their way in and out of any conversation, showing their vast knowledge about almost every topic but never coming across as arrogant or impatient.

To me, he was an example of what chess really needs – a friendly person, well-spoken, well-dressed, knowledgeable, interested in the world, happy talking to others and interesting to talk to.

One occasion stands out in my memory when I think of Bora Ivkov. Several years ago, he spoke at the promotion of my father’s book about Bobby Fischer and his time in Belgrade during the 1992 rematch with Spassky (at the time, my father was closely involved in the event and covered it as a journalist, spending a lot of time with Fischer). One of the guests at the promotion was a famous opera singer from Serbia, Jadranka Jovanovic.

Bora started by saying how in one tournament in the 1950s in Latin America (I can’t remember which one), he was rushing to finish the game so he could go and see – of all the things – a boxing match! What was even more surprising was that after the match Bora went to see a classical music concert. Now, boxing and classical music are two things you don’t place together, let alone someone seeing both in one evening. Bora shared this story as a prelude to another one: he was flying back to Europe from a tournament and, during the long-haul flight, most of the players took out their pocket sets and played or analyzed games. However, Ivkov, at some point, noticed an unusual hat which belonged to one of the female passengers a few seats in front… ‘I was so intrigued that during the whole flight, I was trying to find a way to politely approach that woman…’ As he, later on, found out – that woman was the very person present at the book promotion, the opera singer Jadranka Jovanovic!

And, for me, that is Bora Ivkov – not just a great chess player but an amazing fountain of interesting stories about life, people and places.

Back in 2017, I interviewed him for the British Chess Magazine, which I edit. As I sat down to write this obituary, I read the interview and looked at my notes. We discussed famous players, events, topics, chess and computers, as well as life in general. The interview was so extensive that I had to break it down into two parts. Here I share a few of the things Bora said, which should be noted in the history of the great game.

Ivkov, in his own words: “My whole playing life I did not understand chess”

In one of the first sentences in that interview, Bora Ivkov summed up his chess life: “To be honest, my whole playing life, I did not understand chess. For me, chess was a way to see the world, and there are so many beautiful things to experience and learn out there… There are possibly two things more beautiful than chess – music and women. But, like music and women, chess needs understanding. And there are some great people who understood the link between chess and life so well…”

As for himself, Ivkov never thought he was someone to look up to when it comes to building a chess career. “I am not a good example of a chess player. I’m an anti-example! Months passed with me not looking at the board in times when I was at my peak. I was interested in sports, movies… I would rush to finish a game just so I could go and listen to a performance of a French pianist I loved. I liked going to museums, theatres, boxing matches, football games. In my time, chess could have been played at an amateur level. Meaning that you could play without spending too much time studying it.”

On Lasker, Averbakh, Keres, Tal, Fischer and today’s chess

In the interview, we spoke about almost all the greatest names of chess. Here are Ivkov’s reflections on a few of them.

As someone who “spent most of his time living in the past” Ivkov seemed to be most fond of Emanuel Lasker, or, rather, his path in life: “In the old days it was possible to make pauses in chess, learn something different and become something more than a human chess machine whose whole world begins and ends in 64 black and white squares. Emanuel Lasker managed to do that exceptionally well… Lasker was a figure, a character. Almost everyone else is only a chess player.”

Ivkov considered today’s players to be “too one-sided – only interested in chess”. He also wasn’t fond of the atmosphere in top chess events, saying that players today “are more like basketball stars who are ushered into the arena and then escorted out, with fans feeling a bit uncomfortable, gazing at the players passing by, trying to catch their look so they could ask for an autograph”.

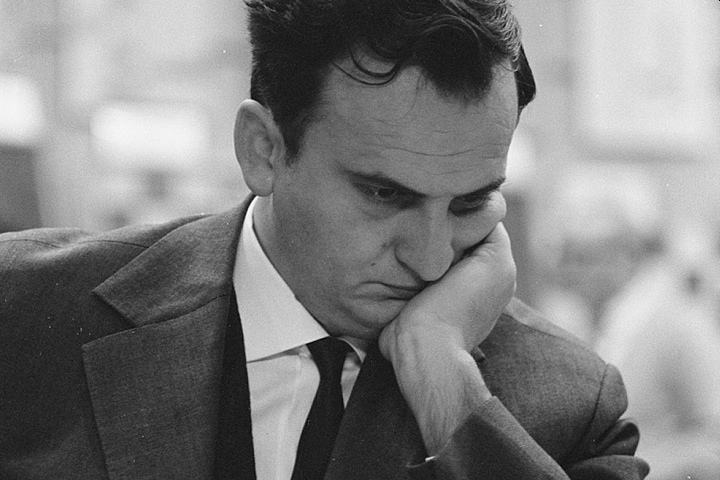

Photo: Francis Raymund Haro

Photo: Francis Raymund Haro

As Yuri Averbakh recently celebrated his 100th birthday, it seems appropriate to mention what Ivkov said in the interview about him: “Not only an excellent player who participated in the amazing Zurich 1953 Candidates tournament, but also a great author in the field of chess theory and chess life in general. A tall man, over 6’3″, he was very good-looking, and I remember Gligoric describing him as Apollo. His body was like a Greek statue!”

When it came to manners, Ivkov considered Paul Keres to be the “greatest gentlemen in chess”: “He carried himself in a very gracious and gentlemanly way. A very kind person. I played four games with him and lost all of them! But it was a pleasure to lose to him as he was so gracious.”

Ivkov was very close to Mikhail Tal, who frequently played and appeared in Yugoslavia at the time. “Tal left the strongest impression on me… People only look at results, but they don’t realize that Tal played with a third of his strength! He had health problems during the greater part of his life. Imagine if he had been healthy as Spassky – who is his peer and who was also an athlete?! He was probably the greatest player who also knew how to enjoy life! Even computers today don’t have the same breadth of ideas and creativity as Tal.”

On Fischer (whom he defeated twice), Ivkov was blunt: “He was a strange person. A recluse interested purely in chess and nothing else… If we agree that the line between a genius and a mad person is very thin, Fischer was on the fence there. I cannot say that he was crazy, but I also cannot claim that he was a completely sound person.”

Reiterating that he is more of a fan of the past than the present, Ivkov pointed to one thing which distinguishes the play of the current generation compared to the “good old days”: ‘They all play like Fischer, meaning – they play until the end! Every position! In my day, when there is a dull position you would simply draw as there was no point in tormenting yourselves. Even Botvinnik would draw! But, today, they play and… win.”

When it comes to computers, Ivkov thought that “they gave something and took something from chess” but the fact that computers are now stronger than men is irrelevant: “A plane is quicker than a man, but we still remember Usain Bolt!” In a more recent conversation – in a café in Belgrade, sitting with Grandmaster Ljubomir Ljubojevic and my father, the three debated on whether chess was better “in the old times” or nowadays. Ivkov summed it up: “The chess of today has nothing to do with earlier times. True, it’s still played on the same 64-square black and white board, with the same pieces, but now in the times of computers, it is only CALLED chess, but it’s something different.”

Bora Ivkov’s final resting place will be in Belgrade. He is survived by his wife and two children.

Text: Milan Dinic, Editor of the British Chess Magazine