The first of nine rounds of the WR Chess Masters started on Thursday, February 16, at 2 p.m. German time and brought three wins and two draws, one of them fought out over seven hours.

Ian Nepomniachtchi – Nodirbek Abdusattorov ½-½

The game that started in the most combative way ended first. After 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4, the 18-year-old Uzbek’s double-edged 2…c5 was already a fighting proposition, and 3…b5 even more so. Benko Gambit! This is rarely seen at this level.

Fruit of targeted opening preparation, Abdusattorov’s exotic opening choice was not, instead, an intuition. “I hadn’t expected 1.d4,” he explained in the interview after the game. Recently he had looked at the Volga Gambit, “so I played it.”

Perhaps he’d been watching the old main variations that Yasser Seirawan and Elisabeth Pähtz were discussing in the live stream: take the gambit pawn with 5.bxa6 or reject the gambit with 5.b6? Meanwhile, if you let your Stockfish calculate 50 or 60 half-moves deep on the fifth white move, you get shown that the machine likes 5.e3 best. And that was what Nepomniachtchi played.

Abdusattorov explained that after Nepo’s 9.b3, he was out of the book, a mysterious explanation because, according to the engine’s evaluation he had been almost lost two moves earlier:

8.Nxf6 Bxf6 9. Qd5 followed by Qxc5, and black compensation for the two minus pawns is hardly visible. Nepomniachtchi played 8.Nf3 instead.

At first glance, it looked as if the world number two, with two bishops shining magnificently on the black king, was building advantageous prospects despite this missed opportunity. Abdusattorov engaged in loosening his kingside – rightly so, as it turned out.

What looked dangerous was not in practice, and on move 15, Nepomniachtchi had to make a fundamental decision: submit to a repetition of the move or play on without a tangible advantage? 15.Qxe7 after which Black forces a draw by Rf7-f8-f7 or 15.Qg3? Confronted with these choices, Ian Nepomniachtchi took almost fifteen minutes to convince himself that he’d rather take the half-point here than tempt fate after 15.Qg3.

Levon Aronian – Praggnanandhaa 1:0

Most VIPs who make the ceremonial opening move have to watch afterwards that the player takes it back and starts again. Vadim Rosenstein was spared this fate.

The tournament organizer and name giver had agreed on 1.c4 with Levon Aronian. Aronian left the neatly placed pawn in the center of the square without any j’adoubing – expecting a symmetrical English, as he and Praggnanandhaa had on the board before. Instead, a very unorthodox English soon developed.

What Aronian called a “cheap trick” after the game represents the reason why he is one of the most exciting chess players, even at an advanced age (by professional chess standards): his creativity.

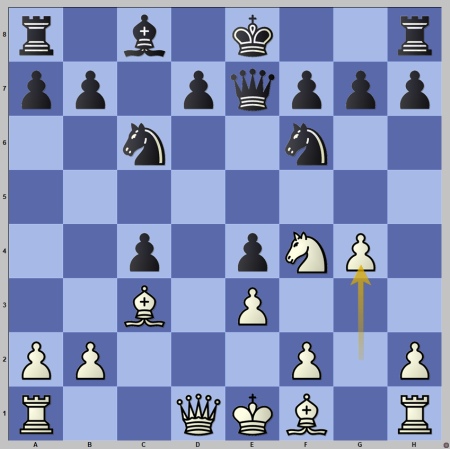

11.g4!? Who would have come up with that?

The idea behind it did not appear on the board. If Black is tempted to play 11…Ne5, 12.g5 Nf3+ 13.Qxf3! follows, and White enjoys splendid compensation for the sacrificed queen. Praggnanandhaa played 11…h6 instead. “Unfortunately, nobody falls for my cheap tricks,” Aronian grinned afterwards.

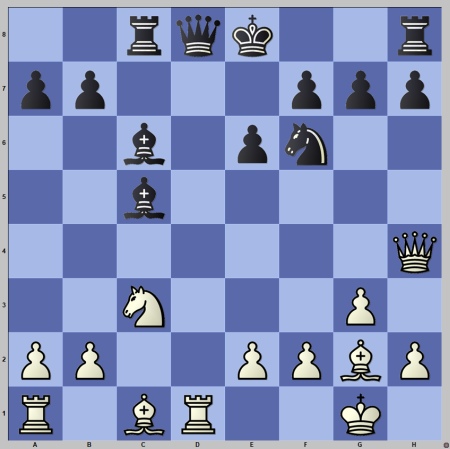

The Indian was on the losing track only five moves later.

Where to put the king? In fact, short castling is not recommended in view of the lever g4-g5 and the Bc3 radiating to g7. The problem: long castling is not recommended either because then f7 hangs.

The solution to the problem: stay cool. 15…Rc8 or 15…Rd8 is considered playable and roughly equal according to chess engines. Aronian agrees: “Not so bad for Black, no need to worry.”

Praggnanandhaa castled long, forfeited the f7 pawn, and quite soon ended up in a desolate and prospectless rook ending that White gradually played out to the full point.

Andrey Esipenko – Vincent Keymer 1:0

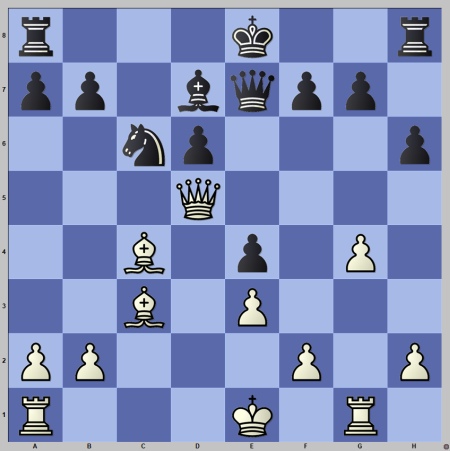

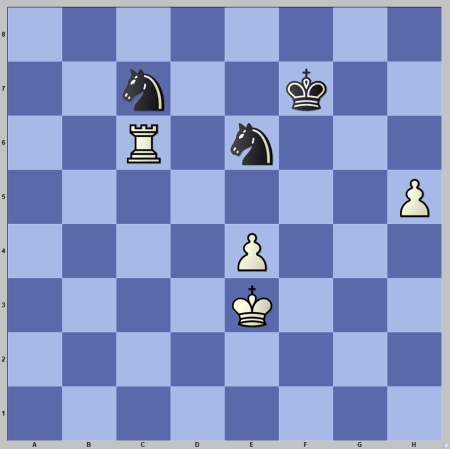

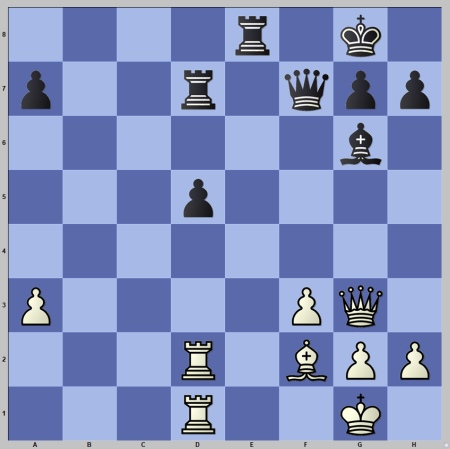

Already in January at Tata Steel Chess, Vincent Keymer had earned the nickname “Marathon Man”. He was usually the last to sit at the board, often defending a critical endgame. At the opener in Düsseldorf, this scene was repeated. The others had finished, but Keymer was still sitting and defending this endgame:

Theoretically, the position is unwinnable for White. But in practice, after six tough hours of chess, things look different. The black task is more than thankless. Yasser Seirawan summed it up in the stream, “Vincent must be suffering.” Naturally, Esipenko kept the thumbscrews on – and was rewarded with the full point after 101 moves.

That it could come to this endgame was the result of a lapse by Keymer in the opening. His move 14…Nd5 looks quite natural, but it has a concrete hook, which Andrey Esipenko threw out on move 16:

16.Nec4! This not-so-obvious piece sacrifice almost leads to Black’s lost position. Black has nothing better than to capture the knight. But after that, the g7-pawn will fall on the black side, h7 too, and Black will find neither coordination nor development.

Wesley So – Jan-Krzysztof Duda 1:0

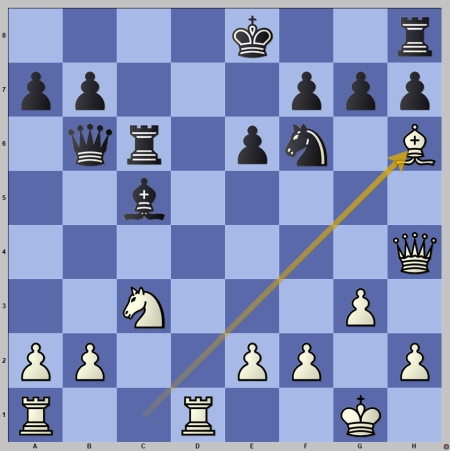

Jan-Krzysztof Duda has to reproach himself for falling into a well-known Catalan opening trap. On the other hand, he is in good company. For example, the former world-class player Ljubomir Ljubojevic or the Dutch top grandmaster Loek van Wely have already seen this position from Black’s perspective after 15.Bh6!

Black has nothing better than the sad retreat 15…Bf8, after which he remains underdeveloped and with his king in the centre – lost in a higher sense. 15…0-0 would be even worse as 16.Bxg7! wins on the spot. The same applies to 15…Bxf2+ 16.Kg2 0-0 17.Bxg7! +-.

To see what Black should have done, we have to rewind two moves:

Not the tempting 13…Qb6, but only 13…Qa5! which is not particularly logical at first sight, gives Black good play. The idea is that white ideas with Bh6 0-0 Bxg7 (as in the game) now don’t work well. Black counters with …Bxf2+, then plays …Kxg7, and White has no check on g5 because of the black queen on a5.

Anish Giri – Gukesh ½-½

White is playing for two results, Elisabeth Pähtz noted in the live stream. Yasser Seirawan explained it more like the storyteller he is. The constellation reminded him of games from the 1984 World Championship match between Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov, in which Kasparov presented the defending champion with the Tarrasch Defense. And the latter, true to his style, enjoyed kneading Kasparov’s isolated d-pawn.

How much Anish Giri enjoyed giving Gukesh a massage à la Karpov is not known. What is certain is that the Wijk winner won’t have been satisfied with the result. His Indian opponent was balancing on edge at times, having to fight off a persistent white initiative due to the opposite-coloured bishops, but saved himself in an endgame with minus pawns. And here, the opposite-coloured bishops were the deciding factor to secure the draw.

Text: Official website

Photo: Lennart Ootes

Offical website: wr-chess.com/